In our last article Local Flatness or Local Inertial Frames and SpaceTime curvature, we have introduced the concept of Riemann tensor, saying that the importance of this tensor stems from the fact that non-zero components are the hallmark of the spacetime curvature.

But before to delve into more details and to give a complete formulation of the most important tensor in General Relativity, it seems reasonnable to get a better understanding of the tensor's concept itself.

Tensor definition

Let us start by giving a definition first:

| A tensor of rank n is an array of 4n values (in four-dimensionnal spacetime) called "tensor components" that combine with multiple directional indicators (basis vectors) to form a quantity that does NOT vary as the coordinate system is changed[1]. |

So we will have to think of tensors as objects with components that transform between coordinate systems in specific and predictable ways[2].

Corollary 1: Combined with the principle of General Covariance, which extends the Principle of Relativity [3] to say that the form of the laws of physical should be the same in all - inertial and accelerating frames, it means that if we have a valid tensor equation that is true in special relativity (in an inertial frame), this equation will remain valid in general relativity (in a accelerating frame)

Corollary 2: A null tensor in one coordinate system is null in all other coordinate systems. In other words, a quantity that we can nullify by coordinate system transformation is NOT a tensor.

Vector in spacetime

As your study carry you along the path of general relativity, you will without doubt run accross the discussions of "covariant" and "contravariant" tensor components.

A good place to begin is to consider a vector, which is nothing else thant a tensor of rank one, and to consider this question:"What happens to a vector when you change the coordinate system in which you're representing this vector?" The quick answer is that nothing at all happens to the vector itself, but the vector's components may be different in the new coordinate system.

One should first recall as preliminary the two following things about vector in space-time, even if it does not really impact the below study on vector components under vector rotation:

- in spacetime vectors are four-dimensional, and are often referred to as four-vectors.

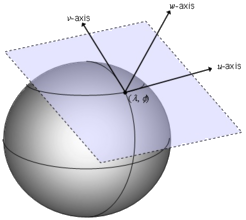

- Secondly, the most important thing to emphasize is that each vector is located at a given point in spacetime. More specifically, to each point p in spacetime, we associate the set of all possible vectors located at that point, and this set is known as the tangent space at p, or Tp.

Nevertheless, it is often useful to decompose vectors into components with respect to some set of basis vectors. Then any vector A can be written as a linear combination of basis vectors

The coefficients Aμ are the components of the vector A in the e(μ) basis.

Vector rotation and contravariant components

Let's consider a coordinate transformation (Lorentz transformation by example) for a given vector V from e(μ) to e(ν') coordinate system.

We have by definition

with Λν'μ equates the components transformation matrix from μ to ν' coordinate systems.

But by definition of a vector (rank-1 tensor) this relation must hold no matter what the numerical values of the components Vμ are.

We can therefore say:

To get the new basis e(ν') in terms of the old one e(μ), we should mutliply by the inverse of matrix transformation Λν'μ

Therefore the set of basis vectors transforms via the inverse transformation of the coordinates or vector components.

This may look quite abstract thus we should switch to more visual/geometrical explanations of this remarkable result.

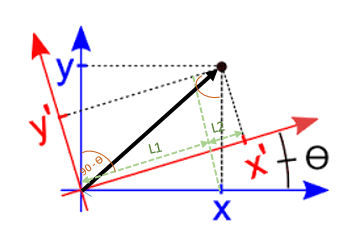

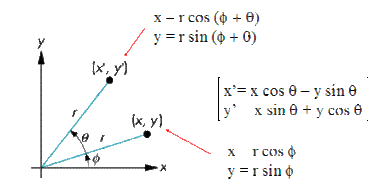

Let us consider the simple rotation of the two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system shown below. In this transformation, the location of the origin has not changed, but both the x- and y- axis have been tilted counter-clockwise by an angle of θ. The rotated axes are labeled x' and y' and are drawn using red color to distinguish them from the original axes.

Our aim is to express the components A'x and A'y[4] of the vector A in the primed/rotated coordinate system relative to the components Ax and Ay in the unprimed/untransformed coordinate system, defined as follows:

If you think to the changes to components Ax and Ay of the vector A, you might come to realize that the vector component A'x in the rotated coordinate system can not depend entirely on the component Ax in the original system. Actually, as you can see in the figure above, A'x can be considered to be made up of two segments, labeled L1 and L2.

So A'x = L1 + L2.

You can see that Ax is the hypothenuse of a right triangle formed by drawing a perpendicular from the end of Ax to the x'-axis. Then it is easy to see that the length of L1 (the projection of Ax onto the x'-axis) is Ax cos θ.

L1 = Ax cos (θ)

To find the length of L2, consider the right triangle formed by sliding A'x upward along the y'- axis and then drawing a perpendicular from the tip of A'x to the x-axis. From this triangle, we should be able to see that

L2 = Ay cos (π/2 - θ)

where (π/2 - θ) is the angle formed by the tips of A'x and Ay (which is also the angle between the x'-axis and the y-axis as you can see from the parallelogram)

So we can finally write A'x = Ax cos θ + Ay cos (π/2 - θ)

A similar anaylis for A'y, the y-component of vector A in the rotated coordinate systems, gives:

A'y = Ax cos (π/2 + θ) + Ay cos (θ)

The relationship between the components of the vector in the rotated and non-rotated systems is conveniently expressed using matrix notation as:

It is very important to understand that the above transformation equation does not rotate or change the initial vector in any way; it determines the values of the components of the vector in the new coordinate system. More specifically, the new components are weighted linear combinations of the original components.

As a final simplification, we can use the Einstein index notation by writing the equation as follows:

This last equation tells you that the components of a vector in the primed/transformed coordinate system are the weight linear combination of the components of the same vector in the unprimed/orginal coordinate system. And the weighting factors aij are the elements of the transformation matrix.

So in our example, we could write the transformation matrix aij as follows:

Basis-vector transformation

Let us try now to figure out how a basis vector transform from the non primed to the primed coordinate when the original basis vector is rotated through angle Θ. We have to be very careful on the meaning of transformation when referring to basis-vector: we are not looking at how the components of the same vector transform from an original to a new coordinate system (above example of aij transformation matrix), but how to find the components of the new (rotated) vector in the original/same coordinate system.

We could show easily through geometric constructions such as those shown precedently that the components A'x and A'y of the new rotated vector (A') in the original coordinate system are:

Multiplying the two matrices = the transformation matrix for finding components of same vector as coordinate system is rotated through angle Θ, and the transformation matrix for finding new basis vectors by rotating original basis vectors through angle Θ reveals the nature of the relationship between them:

There is clearly an inverse relationship between the basis-vector transformation matrix and the vector-transformation matrix, so we can say in that case that the vector components transform "inversely to" or "against" the manner in which the basis vector transform. That's exactly why we qualify these components as contravariant components and why we use the superscript notation.

Quantities that transform contravariantly - Example of differential length element dxi

For any coordinate system in which a linear relationship exists between differential length elements ds, writing the equations which transform between the system is quite straightforward.

If you call the differentials of one coordinate system dx, dy and dz and the other coordinate sytem dx', dy', and dz' the transformation equations from the unprimed to the primed system comes directly from the rules of partial differentiation:

which once again, using the Einstein summation convention could be written as:

This looks like the above components transformation matrix which tells you that the components of a vector in the primed coordinate system are the weighted combination of the components of the same vector in the original coordinate system.

And it can be easily shown that those coordinates transform inversely to how the bases covariate.

As an example, let us consider the changement of coordinates from polar (r, θ) to two-dimensional cartesian coordiantes (x,y):

x'1 = x, x'2 = y, x1 = r , x2 = θ

The componentsfrom old to new system transform according to the following matrix:

Now if you want to transform the set of basis vectors from polar coordinates (er, eθ) to the set of basis vectors (i,j) in cartesian coordinates, you will use the following matrix:

And you can check by yourself that multiplying those two matrices yields to identity

And we should now understand why the transformation equation for contravariant components of vector A is often written as

Contravariant components and dual basis vectors

In Cartesian coordinate system as the one used previously, there is no ambiguity when you consider the process of projection of a vector onto a coordinate axis.

Now imagine a two-dimensional coordinate system in which the x- and y- axes are not perpendicular to one another. In such cases, the process of projecting a vector onto one of the coordinate axes could be done parallel to the coordinate axes, or perpendicular to the axes.

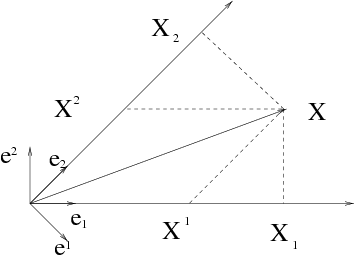

In the diagram below, to understand parallel projections, we have to consider the basis vectors e1 and e2 pointing along the non orthogonal coordinate axes and the projections X1 and X2 of the X vector onto those directions.

In this case, vector X may be written as:

where as seen above, X1 and X2 represent the parallel-projection (contravariant) components of vector X.

Now if we project vector X in a orthogal way along the axes, we come up with the X1 and X2 components of the vector. First remark to do is that the "parallel" projections and the "orthogonal" projections don't have quite the same length and that obviously using the rules of vector addition with X1 and X2 don't form vector X. The perpendicular projections simply don't add up as vectors to give the original vector.

It's then reasonable to wonder if there are alternative basis vectors than e1 and e2 that would allow the perpendicular-projection components to form a vector in a manner analoguous to the contravariant components.

There are, and those alternative basis vectors are called "reciprocal" or "dual" basis vectors. These have two defining characteristics:

- Each one must be perpendicular to all original basis vectors with different indices. So if we call the dual basis vectors e1 and e2 to distinguish them from the original basis vector e1 and e2, you have to make sure that e1 is perpendicular to e2 (which is the y-axis in this case). Likewise, e2 must be perpendicular to e1 (and thus perpendicular to the x-axis in this case).

- The second defining characteristic for dual basis vector is that the dot product between each dual basis vector and the original basis vector with the same index must equal one, so e1oe1 = 1 and e2oe2=1.

The covariant components X1 and X2 made onto the direction of the dual basis vectors rather than onto the directions of the original basis vectors can than be written as follows:

We use superscript notation to denote the dual basis vectors as the inverse tranformation matrix has to be used when these basis vectors are transformed to a new coordinate system, as it is for the contravariant vector components X1 and X2.

Conclusion:

So a vector A represents the same entity whether it is expressed using contravariant components Ai or covariant components Ai:

where ei represents a covariant basis vector and ei represents a contravariant basis vector.

In transforming between coordinate systems, a vector with contravariant components Aj in the original (unprimed) coordinate system and contravariant components A'i in the new (primed) coordinate system transforms as:

where the dx'i/dxj terms represent the components in the new coordinate sytem of the basis vector tangent to the original axes.

Likewise, for a vector with covariant components Aj in the original (unprimed) coordinate system and covariant components A'i in the new (primed) coordinate system, the transformation equation is:

where the dxj/dx'i terms represent the components in the new coordinate sytem of the (dual) basis vector perpendicular to the original axes.

[1] Defintion given by Daniel Fleisch in his Student's Guide to Vectors and Tensors - Chapter 5 - Higher rank tensors p.134

[2] In more formal mathematical terms, a transformation of the variables of a tensor changes the tensor into another whose components are linear homogeneous functions of the components of the original tensor (reference MathWorld article Homogeneous Function).

[3] We recall that according to the Principle of Relativity, laws of physics are the same in any inertial frame of reference.

[4] We will see in the next part of the article why we are superscript index notation for the 'x' and 'y' there; just let us say for now that is because they represent the contravariant components of the vector and this is for distinguishing them from the covariant components Ax and Ay.

Metric Tensor

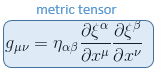

Let us try to illustrate this by the tensor that we have used extensively so far, at least since our article Generalisation of the metric tensor in pseudo-Riemannian manifold, i.e the metric tensor.

where ξα are the coordinates in an inertial referential and xμ the coordinates in a arbitrary referential.

If we now try to express this metric tensor components g'μν in an another arbitrary referential R' with coordinate x'μ, we get:

which is actually conform to the transformation equation of the covariant components of a second-rank tensor

In this expression, T'μν are the covariant tensor components in the new coordinate system, Tαβ are the covariant tensor components in the original coordinate system, and δxα/δx'μ as well as δxβ/δx'ν are elements of the transformation matrix between the original and new coordinate systems. These elements of the transformation matrix represent the dual basis vectors perpendicular to the original coordinate axis.

Index raising and lowering

One of the very useful functions of the metric tensor is to convert between the covariant and contravariant components of the other tensors.

So imagine that you are given the contravariant components and original basis vectors of a tensor and you wish to determine the covariant components. One approach could be to determine the dual basis vectors, performing the perpendicular projections as seen above, but with the metric tensor you have the sorther option to use relations such as

If you wish to convert from a covariant index to a contravariant index, you can use the inverse gij (which is just gij) to perform operations like

This same process works also for higher-order tensors

This is the consequence of a more general mecanism called contraction, by which a tensor can have its rank lowered by multiplying it by another tensor with an equal index in the opposite position, ie by summing over the two indices. In this example, the upper and lower α indices are summed over: